Chelsea Yates

Photos by Mark Stone / University of Washington

A Washington wine industry pioneer, MSE alumnus Jim Holmes shares how he established a world-renowned vineyard thanks to engineering.

“Down to the soil, Ciel is rooted in science and engineering,” says Holmes. Preserving the soil’s essential characteristics is the most important step in the vineyard’s sustainability, and his team has developed an extensive network of sensors to monitor temperature, moisture and soil composition, such as the one next to him here.

Considered one of the state’s first and finest vineyards, Ciel has been providing grapes to some of Washington’s most respected wineries since 1975.

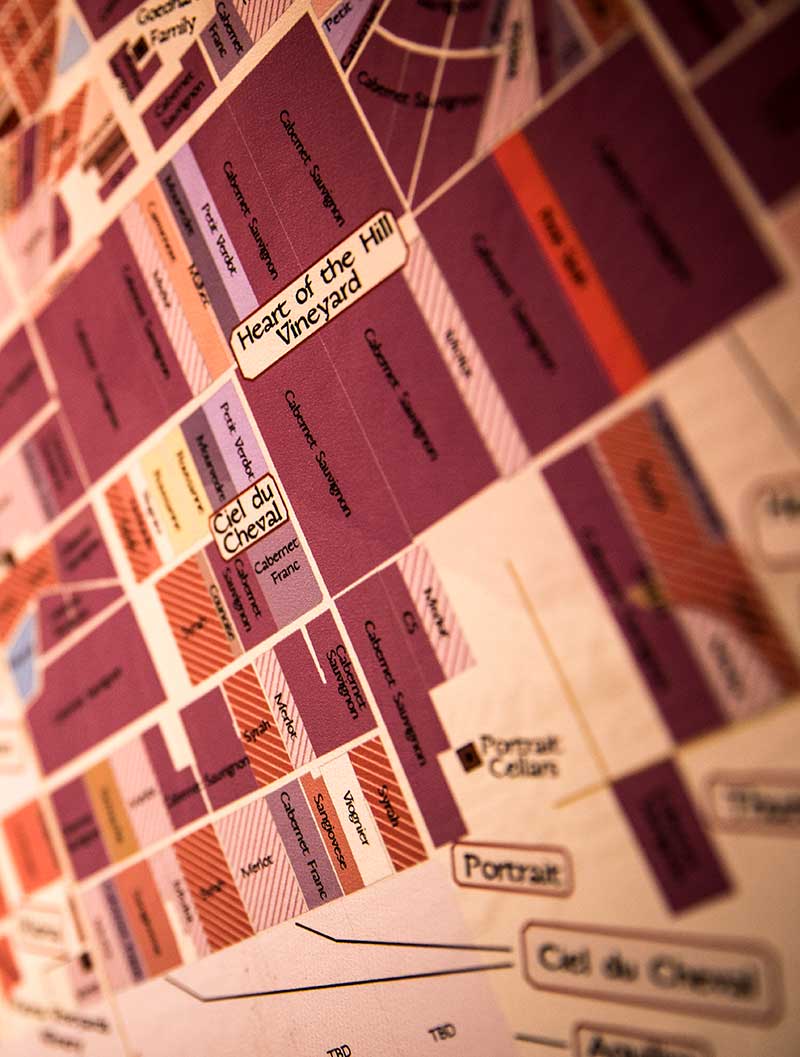

Spanning 120 acres on Washington’s Red Mountain, Ciel du Cheval Vineyard is considered one of the state’s first and finest vineyards. Since 1975, Ciel has provided grapes to some of Washington’s most respected wineries — DeLille Cellars, Mark Ryan, Andrew Will and Cadence, to name a few.

Ciel represents more than 40 years of alumnus Jim Holmes’s passion, determination and commitment to innovation. Holmes, who received his master’s degree in materials science and engineering (MSE) in 1962, has owned and operated the vineyard since its inception. And, he says, it wouldn’t exist were it not for UW Engineering.

We recently spoke with Holmes about how his engineering background has been integral to his vineyard’s success.

COE: Why did you decide to pursue a master’s degree in MSE at the UW?

JH: My family had always been interested in rock collecting, which led to my interest in metallurgical engineering and materials science. After graduating in 1959 with an engineering degree from the University of California, Berkeley, I accepted a job at Hanford. It was an exciting place to be for young engineers; there was a worldwide quest to develop nuclear power as an inexpensive energy source, and much of that work was happening at Hanford. My research team was investigating how structural materials behave in a reactor. I wanted to gain more knowledge of the fundamentals of material behavior, so I decided to pursue a master’s.

It was a wonderful time to do so. The department was transitioning its focus from traditional industrial approaches to emerging technologies in engineering research. The faculty members were young, smart, full of ideas and eager to collaborate with students. The grad student community was superb; we were very supportive of each other.

How did you become interested in wine?

Ciel carefully plans all operations that may affect the soil to ensure that the soil remains true to its original nature. This also allows for different kinds of grapes to be grown in different sections of the vineyard.

I grew up in Northern California surrounded by good wine, so I just assumed that you could get good wine wherever you went. That was not the case in Washington in the early 1960s. Whenever I went home to California, I’d stock up on wine to share with my Hanford research partner and fellow engineer, John Williams. We developed a serious interest in wine but didn’t really have any way to channel it until the early 1970s.

What happened then?

In 1972, John and I invested in some land for commercial purposes and bought 80 acres on Red Mountain. We had no plans to farm it. It was all desert. No one tried to grow anything there.

But we’d been following the work of Walter Clore at Washington State University’s Irrigated Agriculture Research Extension Center. He believed — and demonstrated — that under the right conditions certain types of grapevines could be grown in central Washington. Following his lead, around 1975 we decided to plant a few on our land.

Wow, was it a good thing we were engineers! There was no water source, electricity or roads on our property, so we got to work at what turned out to be a big engineering project: transforming our desert into farmable land. We didn’t have money to hire people so we did all the work ourselves – cleared the land, conducted a geological analysis to determine where to look for water below ground, brought power in from across the Yakima River, established our own irrigation system, did all our own calculations. At first our families thought we were nuts. But then vines started growing, and they began producing grapes.

What was it like being an engineer by day and a viticulturist in your spare time?

Those two identities have always been intertwined for me since my interest in wine and grape growing developed in parallel to my engineering career. When I retired from Hanford in 1994, I was ready to devote myself — and my engineering skills — fully to Ciel.

Ciel avoids taking actions that can harm the environment. The vineyard does not use herbicides and uses practices such as dust control that minimize impact on its neighbors. It has also established a solar-powered irrigation control system.

Ciel’s grapevines “bleed” once pruned in the early spring. In this process, vines draws water up from the soil; once the water pushes against freshly cut surfaces, it oozes out, ridding the vines of minerals and sugars that provided winter frost protection.

Down to the soil, Ciel is rooted in science and engineering. Over the years we’ve developed an extensive network of sensors to monitor soil moisture. We regularly evaluate and analyze plant and soil samples for nutrients. All of this has allowed us to continuously experiment, learn about the land in detail and better understand our soil’s unique composition.

You and your wife Patricia have been advocates for engineering students through your support of MSE graduate students and programs like the Capstone Fund. Why do you stay connected to the UW?

The engineering fundamentals I learned at the UW have provided the backbone for nearly everything at Ciel. I’m proud of the vineyard, and I’m proud to say that I can trace it all back to my engineering studies. I hope that the students we support will one day be able to look back on their time at the UW in a similar way.

We find it very satisfying to support young people interested in engineering research. We are continually impressed by the intellectual talent that we see in today’s students. There is so much curiosity and drive to explore and try new things! It’s very inspiring.

The Husky experience is also a shared experience in our family. Our three sons are all UW alums with degrees in economics, education and political science. My son Richard recently started producing wine from our grapes under the label Côtes de Ciel. So, in a way, I guess you could say that the UW has been with us at every stage of our work – from the first planting to the latest pouring.

Wind turbines installed throughout the vineyard pull warm air down toward the plants to help heat them during colder months.

Learn more about Ciel du Cheval Vineyard at cielducheval.com.

Originally published April 23, 2018