By Sarah DeWeerdt

Nearly every journey in a city, whether by bus, bike, car, on foot, or using a wheelchair, at some point depends on a crucial yet often overlooked bit of urban infrastructure: the sidewalk.

“Sidewalks are at the heart of every community,” says Anat Caspi, director of the Taskar Center for Accessible Technology in the Paul G. Allen School of Computer Science & Engineering. “They represent the fabric that connects all other modes of transportation, any access to recreation, to financial opportunities, to schools, to health opportunities.”

Yet the digital maps and transportation apps that have revolutionized urban navigation over the last two decades contain little information about sidewalks or other pedestrian infrastructure.

Obstacles such as missing curb ramps and uneven sidewalks can be insurmountable barriers to people with disabilities that limit mobility.

That poses a particular problem for people with mobility-limiting disabilities, for whom a cracked or uneven sidewalk or a missing curb ramp can be an insurmountable barrier.

“Sidewalk accessibility is really important,” says Allen School Ph.D. student Ather Sharif, who uses a motorized wheelchair. “Otherwise, how are we going to get around?”

Sharif and Caspi are among a growing group of UW engineering and computer science researchers who are making digital wayfinding more equitable and accessible to a broader segment of the population via a series of projects focused on sidewalks.

The results will not only make cities friendlier to those with mobility limitations, but will also benefit other groups, including seniors, pregnant people, caregivers of young children who use strollers, first responders, and even perhaps delivery robots one day.

“The availability of this information actually serves everyone,” says Mark Hallenbeck, director of the Washington State Transportation Center in Civil & Environmental Engineering.

AccessMap and OpenSidewalks

Caspi, whose background is in bioengineering, became interested in sidewalk accessibility after moving to Seattle and struggling to navigate the city’s steep hills with her daughter, who uses a wheelchair. That experience sparked AccessMap, the first city-scale pedestrian customized wayfinding application.

“The idea was to provide an app that foregrounded the sidewalk environment,” Caspi says. Sidewalks are highlighted; streets and buildings fade into the background.

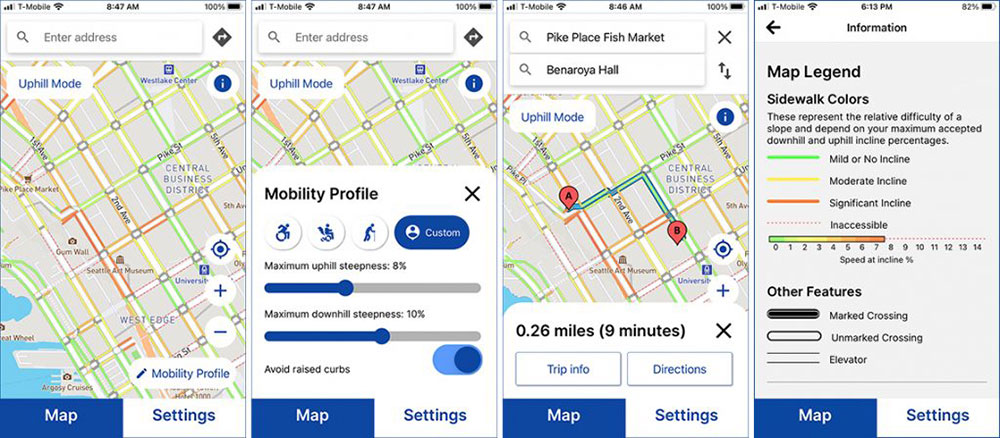

AccessMap uses green-yellow-red color-coding to indicate the difficulty of traversing a given length of sidewalk, similar to the way car-centric maps color-code the heaviness of vehicle traffic. Users can also specify their individual mobility needs and the program will identify customized routes through the city.

AccessMap enables users to select from preset pedestrian profiles or customize their own to obtain directions following an accessible route between Point A and Point B. The different colors shown on the map allow users to determine accessible sidewalk routes at a glance. Images from AccessMap.

The tool currently covers three Western Washington cities: Seattle, Mount Vernon, and Bellingham. The team released a mobile application last December, and is now focused on expanding to other cities in the United States and Latin America.

AccessMap is based on data on sidewalk and curb ramp location provided by city transportation departments — data that tend to be spotty and inconsistent.

“As we tried to expand AccessMap in more areas, we were running into a lot of non-standard data formats,” says Nick Bolten, a Taskar Center postdoctoral researcher.

That situation gave rise to OpenSidewalks, an effort to develop data standards and support tools for sidewalk data. If all cities collected and reported sidewalk data in the same way, it would be much easier to add more cities to AccessMap or other wayfinding tools. Such standards and tools would also prompt more cities to collect sidewalk data and keep it updated, Caspi argues.

OpenSidewalks is currently active in 11 cities, with local teams in each city in charge of collecting and stewarding the data. This helps bring to the fore local idiosyncrasies of the pedestrian network, such as the way wheelchair users rely on elevators in certain buildings to traverse hilly Seattle, or the importance of enclosed, elevated walkways in snowy Minneapolis and St. Paul, Minnesota.

Project Sidewalk and Sidewalk Evolution

Even when cities do collect data on sidewalks, they typically don’t record information about sidewalk condition or other obstacles — such as tree roots, uplift, cracks or substandard curb ramps — that can pose a major barrier to mobility.

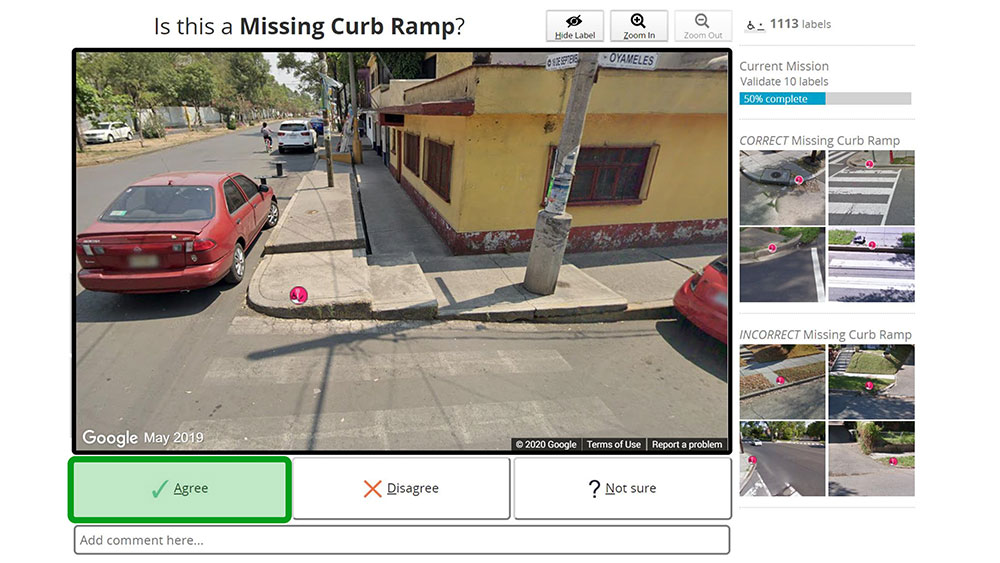

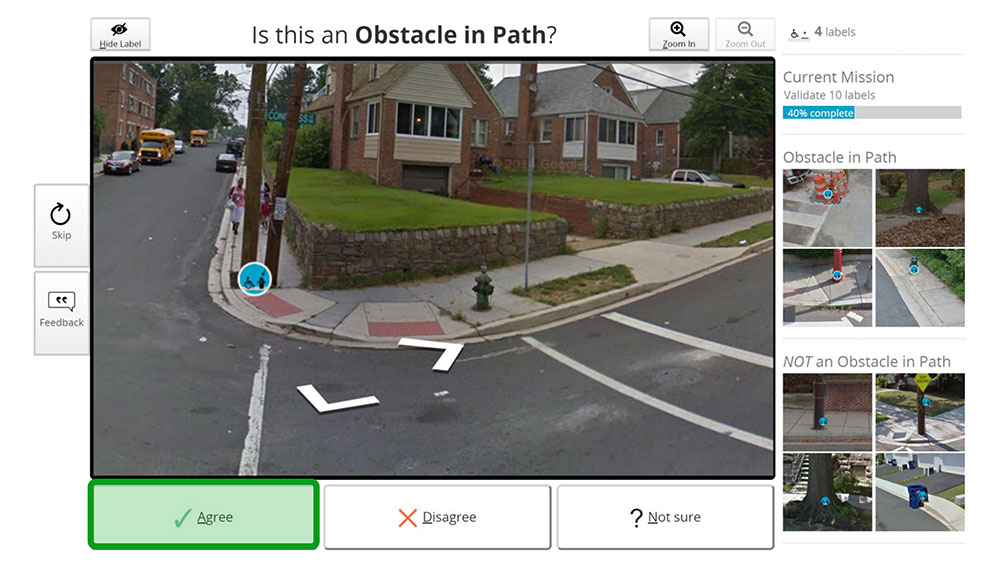

Enter Project Sidewalk, an online crowdsourcing game that virtually immerses volunteers into Google Streetview to evaluate sections of sidewalk in detail.

Project Sidewalk uses online map imagery and remote crowdsourcing for collecting and validating data about sidewalk conditions. Volunteers are given missions to explore and correct data, such as identifying missing curb ramps or pathway obstructions as shown here. Images from Project Sidewalk.

It gives you missions and that's how it scaffolds the experience, and also tries to make it fun and engaging,” says project lead and Allen School associate professor Jon Froehlich. At the UW, much of this work is taking place through the Center for Research and Education on Accessible Technology and Experiences (CREATE).

Project Sidewalk launched in 2012 in Washington, D.C., and is currently active in seven cities, including Seattle. Volunteers have collected 600,000 data points so far, which Froehlich’s team is using to train computer vision algorithms to evaluate sidewalk condition.

“Assigning this task to AI would transform how we’re able to compare accessibility across cities,” Froehlich says. He envisions using Project Sidewalk to perform quick, initial accessibility audits for cities around the world. The data could also be incorporated into other sidewalk-oriented apps and tools, such as AccessMap.

A related effort in Froehlich’s lab, Sidewalk Evolution, aims to apply computer vision to images to track changes in curb ramps over time. The approach could then be applied to tracking temporal changes in other kinds of images, explains Sharif, who is working on the project.

Sidewalk Evolution aims to apply computer vision to images to track changes in curb ramps over time, as seen here in images taken of the same intersection from 2011 and 2015. Images from Project Sidewalk.

But it’s not just a matter of academic interest.

“Advocates in the disability world could use that data to make the case for better accessibility,” Sharif says. Data from this and other sidewalk accessibility projects could spark conversations around the equitableness of accessibility, and point out which neighborhoods and populations lack access to good pedestrian infrastructure, he and other researchers say.

Expanding transportation equity

Sidewalk accessibility data also needs to be linked to the broader transportation network. One effort to do that is the Transportation Data Equity Initiative (TDEI), supported by an $11.45-million, multiyear award from the U.S. Department of Transportation.

TDEI aims to develop data standards for three elements of the transportation system: sidewalks (that is, it represents the next iteration of OpenSidewalks); navigating transit centers; and paratransit, which includes on-demand shuttles and community transit on Native American reservations.

The initiative will refine and help gain adoption of international data standards in all three areas, as well as develop procedures to collect, store, update and publish these data as a feed.

“There's a lot of work to be done,” says Hallenbeck, who co-leads the initiative with Caspi.

Similarly, an unrelated project led by Sharif, UnlockedMaps, visualizes the accessibility of urban rail transit, highlighting features such as accessible restrooms and restaurants. It also tracks real-time elevator outages at transit stations — data often missing from digital maps.

Following the principle of “nothing about us without us,” Sharif and his team have been seeking input from users with mobility disabilities to guide the next phase of the project.

“After seeing elevator outage information on the map, I realized it is an important feature since it impacts a lot of people,” says computer science undergraduate Luna Chen, who is conducting user experience research for Unlocked Maps. She adds that working on UnlockedMaps has sparked her interest in other accessibility-related projects.

It’s an energy that many members of the UW Engineering community share.

“There's so much potential in this space, because it's so underserved,” Bolten says. “And there's always a million directions that we envision going.”

Creating a healthier and more just world

Engineering for the community is a key priority of the UW College of Engineering.

Originally published March 7, 2022