By Ed Kromer

Looking beyond incremental innovations in energy storage technology, Jie Xiao wants to catalyze a robust domestic battery industry — from mining to manufacturing.

Jie Xiao, a widely respected energy storage researcher, is working to catalyze a viable battery manufacturing industry in the U.S. Photo: Mark Stone / University of Washington

Build a better mousetrap, the old saying goes, and the world will beat a path to your door.

Build a better battery… and the multitudes should arrive in an endless stream of autonomous electric vehicles.

Only, it’s not that simple with energy storage.

Most battery innovations begin in academic environments that are designed for discovery rather than the cost, time and scale pressures of industry.

“It’s easy to make a five-gram sample in a lab,” says UW Engineering Vice Dean Jihui Yang, an expert in energy conversion and storage. “But what’s much more challenging is to achieve the kind of uniformity needed to deliver battery performance on a scale of tens of tons. It’s not just about chemistry and composition. The more important question is: How do we scale this technology? How do we put innovation into practice?”

This challenge has become the singular mission animating Jie Xiao, the Boeing Martin Professor in Mechanical Engineering, who joined the UW in 2024. Xiao is one of the nation’s most respected — and connected — battery innovators. And she is quickly becoming a fulcrum of coordinated activities around campus and beyond to translate academic innovations into a viable domestic industry.

“Traditional battery R&D — including my own — operates on an atomic level of understanding. And we have developed tremendous knowledge,” says Xiao. “But we need to turn this knowledge into resilient manufacturing science and engineering, which is a very different prospect.”

A query that launched a career

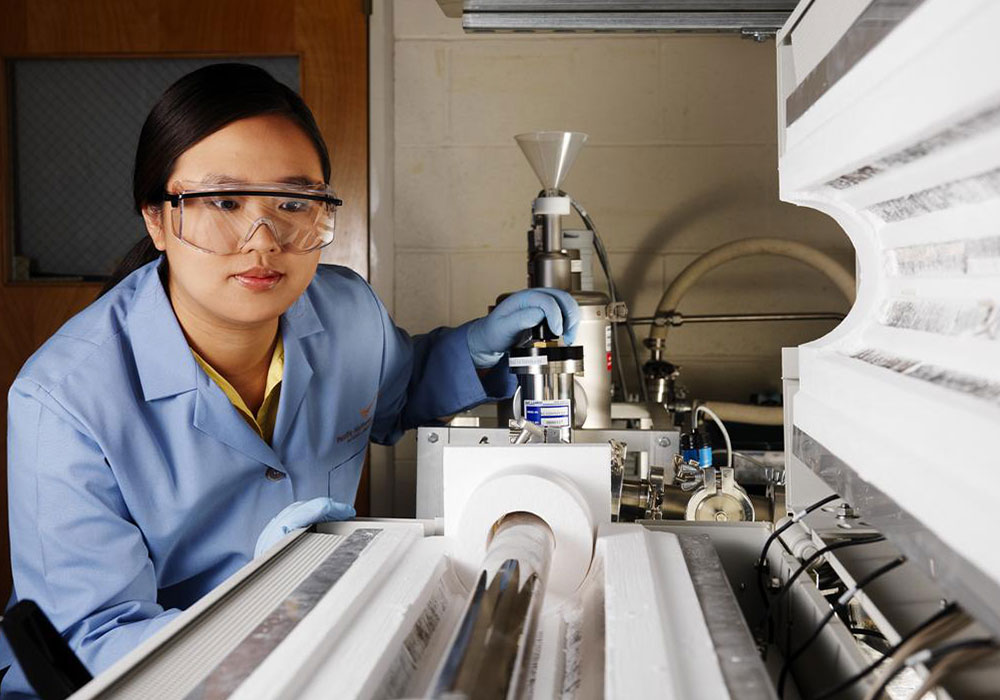

Right after earning her Ph.D., Xiao joined the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory to help launch its energy resilience initiative. Photo courtesy of PNNL

Xiao’s career in electrochemical energy storage began almost by accident. As an undergraduate studying physical chemistry two decades ago, she stumbled upon a paper on hydrothermal synthesis of battery materials by M. Stanley Whittingham, who would win the 2019 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his role in developing the lithium-ion battery.

Intrigued, Xiao emailed Whittingham a long list of questions. To her surprise, he replied — in great detail — the next day. “It was so touching,” she recalls. “I was just some random student on the Internet.”

The conversation continued, and Xiao soon joined Whittingham’s research group at Binghamton University.

After earning her Ph.D., she went to work at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL), where she helped launch efforts to develop more efficient energy storage materials and technologies. Eventually rising to Battelle Fellow, she worked across scales — from batteries as small as a grain of rice and as thin as a strand of hair to systems supporting grid energy storage.

From mining to manufacturing

A few years ago, the natural resources company Albemarle collaborated with Xiao to develop high-energy battery materials using advanced lithium salts. The research, supported by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), discovered a unique sublimating property of lithium oxide that dramatically reduced the time and energy required for conventional battery manufacturing.

Xiao's lab is using AI to accelerate the processing and scale-up of energy-bearing raw materials, such as malachite. Photo: Mark Stone / University of Washington

“Not only did the research turn out to be very successful, it also completely changed my mind set on fundamental research,” Xiao says.

She began pursuing “cost-focused” fundamental science, which considers the real-world issues of industrial production. She likes to use a baking metaphor to explain this new approach: If you wanted to use a recipe for 60 cookies to bake 60,000 cookies, you’d need to make significant adjustments in the ingredients and methodology to minimize cost and time while producing quality treats with consistent look, texture and taste.

It’s the same with batteries. Within their common anatomy of anodes, cathodes and electrolytes that capture and convey energy, there can be infinite combinations of component materials, processes and reactions. These are now well understood — in laboratory conditions. Manufacturing batteries at industrial scale introduces a different set of constraints. And accounting for them is essential to closing the gap between lab and industry.

“It’s a golden opportunity for researchers,” Xiao says. “We have the tools. We have the knowledge. But we can no longer do research without considering the application.”

Getting in the battery race

She says this with some urgency. Demand is exploding for batteries to power everything from cell phones to drones, heat pumps to power tools, EVs to AI data centers. And most of this demand is currently being met by China, which has an enormous lead in manufacturing energy storage.

It’s a golden opportunity for researchers. We have the tools. We have the knowledge. But we can no longer do research without considering the application.”

In response, Xiao is catalyzing construction of a robust supply chain and industry in the United States.

A recent paper, co-authored by Whittingham, engaged industry leaders to outline the scientific challenges for mining and manufacturing — with the intent of fostering research that directly supports industry. She just launched a new journal, sponsored by the DOE, dedicated to furthering energy storage manufacturing science.

Through her joint appointment with PNNL, Xiao continues leadership roles in two DOE-supported consortia dedicated to increasing battery capacity and hosts regular industry workshops to understand challenges and opportunities in battery manufacturing.

At the College of Engineering, she has joined a cohort of energy storage researchers that includes Yang, Jun Liu, Corie Cobb, John Kramlich, Aniruddh Vashisth, Ting Cao and UW-affiliated Alejandro Franco, supported by experts in AI, robotics and advanced manufacturing.

And Xiao is leading the UW’s forthcoming Intelligent Battery Engineering and Automated Manufacturing certificate program, with support from the DOE.

“We need to unite and develop a core strength to become a national leader in energy storage manufacturing,” Xiao says. “I think this is a great opportunity for the UW.”

It’s also a great opportunity for Washington state, which is rich in natural resources, biomass and brain power. With companies such as Group14 establishing a foothold in advanced battery materials and plenty of local tech industry demand for energy resilience — why not headquarter a national industry right here?

Xiao hopes these activities will encourage local startups and attract established companies to the state: “We just need to connect the components to build a healthy battery ecosystem.”

Paying it forward

Xiao’s lab is a microcosm of her larger dream. Inside this bustling hive, students lean over electroplating machines and laser microscopes and an air-fryer-sized furnace that can reach 1200 degrees centigrade in minutes to experiment with various critical minerals and materials. They have come here to pursue their own curiosity and career goals in a community of inquiry. And Xiao ensures they get the kind of welcome she once received from a future Nobel laureate when she was just finding her way.

“It’s amazing how one person can change your path,” she says. “Professor Whittingham’s patience and kindness inspired me. So, no matter if they’re in high school, an undergrad, a master or doctoral student, if they want to discuss science with me, I will always say yes.”

Xiao is intentional about mentoring students, who explore many facets of battery design and production. For newcomers, she has developed a virtual reality game to simulate battery assembly in a safe context. Photos: Mark Stone / University of Washington

One such conversation attracted Paola Manjarres, a master’s student in materials science and engineering, to the Xiao lab, where she is upskilling herself in battery manufacturing. “Professor Xiao has a great balance of guidance and independence,” Manjarres says. “She provides clear direction while giving us freedom to make decisions and take ownership of our projects, which has helped me grow as a researcher.”

Manjarres plans to work as a battery engineer — an outcome that aligns with Xiao’s goal of training researchers who can help bridge the gap between discovery and production.

“I want to inspire more people to study in our field,” Xiao says. “It’s going to take a lot of talented people from different backgrounds working together to realize a thriving domestic energy storage manufacturing industry and supply chain.”

Read more engineering and industry stories

UW Engineering faculty and students are supporting the industries of today and tomorrow, transforming research into real-world solutions for the public good.

Originally published January 26, 2026