By Ed Kromer

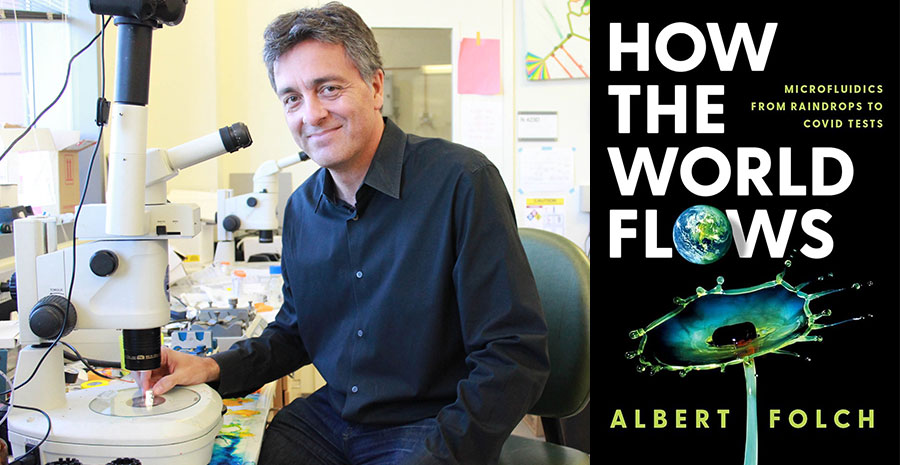

In his new book, “How the World Flows,” Albert Folch explores the miniature liquid networks that power natural phenomena, essential innovations and advanced biomedical devices.

Albert Folch is the author of "How the World Flows." Photo by Ilsolde Raftery, courtesy of KUOW

Rainbows and rubber trees. Aquifers and fountain pens. Gauze pads and glucose strips. Candle wicks and carburetors. Pregnancy tests and 3D printers. Dialysis machines and DNA sequencers.

What’s the common denominator?

Each is enabled by microfluidics, miniature networks of liquids whose stable properties, at tiny scale, are essential to powering the natural world — and much of the manufactured world, too.

And each is explored in Albert Folch’s new book, “How the World Flows,” which invites readers to peer through the microscope into what he calls the “Lilliputian world of fluids at small scales.”

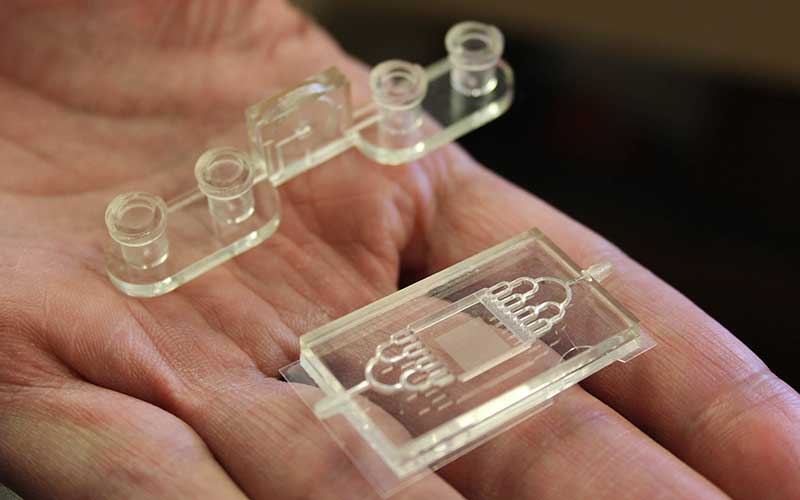

A colorful microfluidic research device from the Folch lab. Dennis Wise/UW Photography

Folch, a professor of bioengineering, has decades of experience in this miniscule world. His lab develops organ-on-a-chip technology, using microfluidics and robotics to test cancer therapies on dust-speck-sized “cuboids” of living tumor biopsies arranged on 3D-printed plates with tiny channels, wells and valves that simulate the body’s microenvironment.

Folch’s passion for microfluidics flows through the bindings of “How the World Flows,” which delves into the minute liquid networks underpinning modern engineered devices, ancient human inventions and sublime natural phenomena. He uses non-technical language and stories featuring an eclectic cast of historical figures to make each chapter’s physics-based concepts approachable.

We recently sat down with Folch to ask him a few questions about the book.

What inspired you to take on this project?

I love to write. After soccer, it’s my favorite pastime. I had written “Hidden in Plain Sight” (a more technical academic work examining modern microfluidic devices) when the pandemic hit and everyone was stuck at home.

But I knew that book did not tell the whole story of microfluidics. My wife, Lisa, a neurobiologist who works in the lab, was pushing me to do another. She said, ‘You have a more beautiful story to tell.’

How did you decide on the book's scope, structure and tone?

‘How the World Flows’ is a dazzling exploration of the myriad ways that microfluidics underpins our world.”

Microfluidics is much bigger than just the modern medical devices. The term was coined in 1992, but microfluidic devices had been around long before then. And not only for medical science. Think about the carburetor, a beautiful microfluidic invention from the 1880s that atomized fuel into droplets surrounded by oxygen to ignite more easily. Or go much further back to the candle wick, which is based on the microfluidic property of capillarity.

The book is divided into three big themes: modern engineered microfluidic devices, early microfluidic inventions and so many beautiful examples from nature. Like trees drawing nutrients from their roots to their highest branches using capillary action and, as they grow taller, evaporation. Or water droplets refracting light to project rainbows.

You start the book with droplets and rainbows. Why?

I thought the simplest microfluidic system you can image is a droplet. Droplets are everywhere and have existed forever. And each contains essentially a tiny chemical laboratory. I wanted to start with the rainbow as a familiar introduction to the physical properties of droplets. And it happened that rainbows had been studied by Isaac Newton in the 1660s.

An array of illustrative stories feature both renowned and unknown protagonists. Do you have a favorite?

The biggest challenge with the book was finding good stories to illustrate each concept. One that I think works well is “The Man Who Wore a Sanitary Pad.” A loving husband in rural India lost everything in his determination to design for his wife a simple machine to produce inexpensive sterile menstrual pads with plant cellulose. In the end, he overturned a taboo, won a national prize for his invention and returned to his village as a hero. It’s a really inspiring story.

The Folch Lab is using 3D printing technology to produce precision microfluidic networks for biomedical research. Dennis Wise/UW Photography

I also like the chapter “Every Breath We Take,” which centers on filmmaker Craig Foster, whose documentary about his friendship with an octopus introduces the exceptional microfluidic breathing abilities of the animal kingdom.

And “The Sounds of Microfluidics” opens with Roger Payne, who discovered whale songs in the 1970s, as prelude to the microfluidics behind auditory systems that all vertebrates have in common.

All the stories are meant to show what I’m always telling everyone: Microfluidic systems are everywhere. Our ears, our lungs, our capillaries — even our cells — are all microfluidic devices.

What do you hope comes out of “How the World Flows?”

When people grab their phone, they have an intuitive understanding of the microelectronics that are hidden beneath the screen. My biggest hope is to help make microfluidics a buzzword that everyone knows. Because, to my mind, the impact of microfluidics on our lives is even greater than microelectronics. Many technologies we rely on every day are guided by microfluidics. Our bodies, our plants, our planet — life would not exist without microfluidics.

Originally published January 5, 2026